After a Tragedy in 2002, Special Forces Soldiers Learned That Armed Drones Are a Combat Necessity

Sep 17, 2025

By Richard Whittle

Why the Predator is here to stay.

The Battle of Takur Ghar began three days into Operation Anaconda—an attempt by thousands of U.S. and allied troops to encircle Al Qaeda and Taliban forces in Afghanistan’s Shah-i-Kot Valley in March 2002. Small reconnaissance teams were being deployed to establish observation posts in strategic locations, where they could direct U.S. air power against enemy targets.

U.S. Navy SEAL Neil Roberts was the first casualty of the Battle of Takur Ghar.

At about one o’clock in the morning local time on March 4, Razor 03 (the call-sign for a U.S. Army Boeing MH-47E helicopter) tried to insert one such team at Takur Ghar, a mountain of more than 10,000 feet. But U.S. forces were unaware it was an enemy stronghold, where Al Qaeda had positioned fighters to fire on helicopters and troops operating in the valley below. While landing, Razor 03 was hit by a rocket-propelled grenade and gunfire, causing U.S. Navy SEAL Neil Roberts to fall from the helicopter. The heavily damaged MH-47E then made an emergency landing about three miles away.

What came next was an intense 17-hour fight at the top of Takur Ghar. The legendary battle will be represented by two artifacts on exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum’s Modern Military Aviation gallery, which opens next year on July 1. One of the artifacts is a General Atomics MQ-1 Predator (initially designated RQ-1), the first of its type to be armed and used to attack ground targets with AGM‑114 Hellfire missiles, a weapon designed to be fired from helicopters. The Museum’s MQ-1 flew 196 combat missions in Afghanistan.

The second artifact, which will be displayed on a mannequin, is a desert-tan flightsuit of the type worn by helicopter pilots of the U.S. Army’s 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR). Organized in 1981 and known as the Night Stalkers, the 160th regiment was used intermittently for special operations in the 1980s and 1990s. According to an official history, between November 1993 and October 2001, the unit flew only non-combat missions.

But the war in Afghanistan transformed both the MQ-1 and the Night Stalkers from supporting roles to leading actors in the drama of 21st century warfare. The lead curator for the Modern Military Aviation gallery is Michael W. Hankins, who specializes in post-World War II military aircraft. He notes that the displays relating to the war on terrorism will depart from the exhibit’s overarching theme. “We’re telling the story of American military aviation from the end of World War II up until today,” says Hankins. As such, many of the nearly 200 items in the gallery reflect how nuclear weapons and global reach affected the evolution of aviation technology after World War II. The 160th uniform and the MQ-1 reflect the fact that the “perceived threat to the United States in the early 2000s is much different than it was at the height of the Cold War,” says Hankins.

Roger Connor, the Museum’s curator for drones and rotorcraft, says the MQ-1 and the 160th uniform are apt artifacts for telling the most recent history of U.S. military aviation. “Having the Predator and the 160th uniform really speak to this new moment in warfare that we see in early 2002, when the war on terror is becoming very dependent upon the changes in U.S. military aviation that have been wrought in the post-Vietnam, post-Reagan era,” says Connor. “So, we see much greater emphasis on UAS (unmanned aerial systems). We see much greater emphasis on special operations capability: the ability to conduct operations without large-scale ground forces.”

An MQ-1 Predator, armed with AGM-114 Hellfire missiles, flies a combat mission over southern Afghanistan. The MQ-1 played a crucial role in the Battle of Takur Ghar.

A Tale of Two Artifacts

Both the MQ-1 Predator (tail number 3034) and the 160th uniform have been in the Museum’s collection for some time. The Predator, manufactured by General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, was displayed in the former Military Unmanned Aerial Vehicles gallery at the Museum in Washington, D.C., from 2008 to 2018. The Night Stalker uniform has been exhibited at the Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia.

The Predator is a long-endurance unmanned aerial vehicle that can transmit color, black-and-white, and infrared imagery from an onboard video camera and infrared sensor to a ground control station. It was designed solely to perform intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance flights. But in the summer of 2001, a team of technology specialists with a U.S. Air Force rapid-innovations unit known informally as Big Safari (officially, the 645th Aeronautical Systems Group) modified Predator 3034 to carry two Hellfire missiles. A Big Safari expert nicknamed the “man with two brains” (real name withheld) then devised a patchwork of undersea fiber-optic cable and Europe-to-Asia satellite signals, enabling pilots and sensor operators in a ground control station parked at CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, to remotely fly the newly armed Predator over Afghanistan. The goal was to give policymakers a way to kill Osama bin Laden.

The Air Force and civilian contractor crews who flew 3034 and two other armed MQ-1s over Afghanistan from the CIA parking lot never got a shot at bin Laden. But they made other uses of the new weapon—igniting a drone revolution still unfolding today.

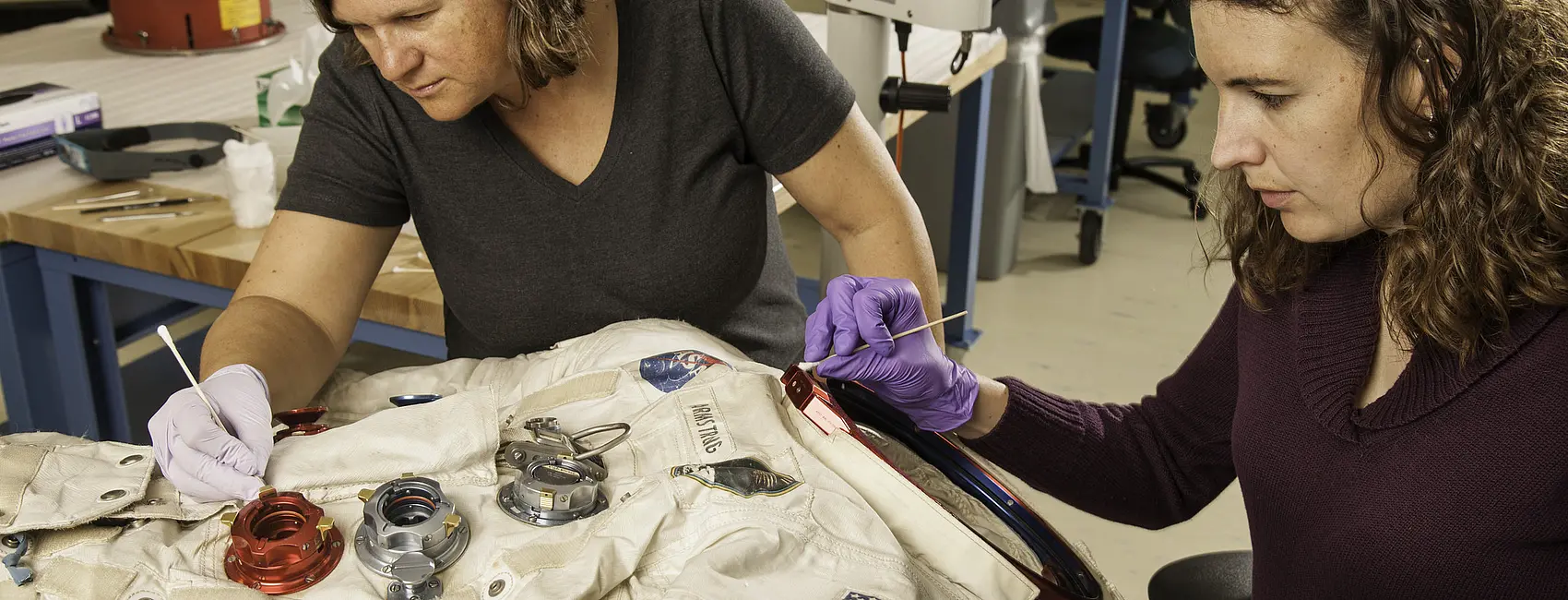

The Night Stalkers usually fly in darkness, often on short notice, frequently at ground-hugging “nap-of-the-earth” altitude, and usually both carrying special operations troops and providing armed escort for them on risky missions. The Night Stalker uniform displayed at the Museum was set up with the assistance of Alan C. Mack, author of Razor 03: A Night Stalker’s Wars, a memoir of his 17 years as a 160th pilot during a 35-year Army career. “It’s just a generic uniform, but I marked it up as if it were mine,” says Mack, who retired at the rank of Chief Warrant Officer 5. “My blood type is [written] on the boots, and my initials are on the back of the boots. The vest itself is set up how I wore mine. There’s some variability in how people set up their equipment.”

Alan Mack flew MH-47Es while serving in the U.S. Army. He has written a memoir about being a pilot in the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment.

Besides the basic flightsuit, air crew coat, boots, flying gloves, and helmet, the display includes gear and weapons that Night Stalker pilots carried in the early 2000s, depending on the mission: an armored vest, a survival vest, night vision goggles, a knife with a scabbard, a pistol and holster, M-16 and M-4 carbines, and pouches for ammunition, a radio, a first aid kit, and other items.

Mack says he and other pilots who flew in Afghanistan in the early 2000s also used or wore non-military items to cope with the high altitudes and cold temperatures when flying over the Afghan mountains. “The GPS, for example, was just a Garmin that they bought,” says Mack. “Some of the cold weather gear was straight from North Face or Columbia.”

The high altitudes often required 160th crews to use oxygen masks. But the sort worn by fighter pilots became very cumbersome with night vision goggles, which also strap onto the user’s head. “So, we ended up going with a commercial, off-the-shelf product of an oxygen bottle with nasal cannula,” says Mack. “Turned out that at our altitudes, 25,000 feet and below, that was sufficient to give you enough supplemental oxygen, and it was much more comfortable to wear for hours at a time versus an old-fashioned mask. We looked like a bunch of emphysema-ridden pilots before they quit smoking.”

The 160th regiment, like the Joint Special Operations Command it falls under, emerged in the aftermath of several military reforms following the humiliation of the failed April 24, 1980 mission to rescue 53 Americans held hostage in Iran. “It was recognized after Operation Eagle Claw that the United States Army needed an elite special operations aviation unit,” says Sean Naylor, who covered special operations for the Army Times.

Initially activated on August 15, 1981, as Task Force 160, the Night Stalkers were one of the first helicopter units to routinely train in darkness using night vision goggles—an often-treacherous task given the quality of goggles of that era.

The 160th’s intensely trained pilots fly three main types of specially equipped, heavily armed helicopters of different sizes: AH-6 and MH-6 Little Birds made by Boeing and several models of Sikorsky MH-60 Black Hawks and Boeing MH-47 Chinooks. Regular passengers on Night Stalker flights include Navy SEALs, Army Rangers, and Air Force special operators. The Night Stalkers’ creed pledges members to be “ready to move at a moment’s notice anytime, anywhere, arriving time on target plus or minus 30 seconds.” Missions to capture or kill high-value targets are a specialty. Two secretly developed 160th Black Hawks equipped with technology to muffle the noise from their tail rotors delivered the SEAL Team 6 members who killed bin Laden. The next month, the Army made Night Stalkers an official designation.

While in Afghanistan, Mack flew the MH-47E Chinook, a special operations version of the massive and powerful CH-47 heavy lift transport. The MH-47E was especially valued in Afghanistan for two reasons: its ability to reach altitudes higher than any other U.S. helicopter and its possession of a terrain-following radar. This feature “provides airspeed, steering, and power commands for the pilots to maintain a desired terrain clearance altitude, selectable by the pilots to fly at 100, 300, and 500 feet above the terrain ahead,” Mack explains in his book.

A 160th MH-60M DAP Black Hawk test fires 2.75-inch rockets. While sharing the same airframe as the MH‑60M, this variant is configured as a highly weaponized platform to provide air support and armed escort during special operations, setting it apart from other Black Hawks focused on transport and utility roles.

Mack says Night Stalker training routinely includes expensive exercises such as flying in the U.S. Rocky Mountains on oxygen, refueling at night over water, and firing powerful weapons that include the M-134 mini-gun—a six-barrel, Gatling-style rotating machine gun that fires 7.62-mm shells at a rate of 6,000 rounds per minute. A special Night Stalker version of the Black Hawk, the MH-60L DAP (direct-action penetrator), can carry varying combinations of 7.62-mm mini-guns plus a 30-mm cannon, 2.75-inch folding-fin rockets, and Hellfire missiles.

The unit’s first combat mission using night-vision goggles was on September 21, 1987, when three AH-6 Little Birds used mini-guns and rockets to disable an Iranian navy vessel laying mines to disrupt oil tanker traffic in the Persian Gulf, enabling SEALs to board and seize it. Two years later, when U.S. forces deposed Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, Night Stalker AH-6 and MH-6 Little Birds helped Delta Force rescue imprisoned U.S. citizen Kurt Muse. A 160th MH-60 then took Noriega to a U.S. Air Force base after he surrendered.

Since most of their missions are secret, the public, unfortunately, tends to remember the 160th for two operations that turned tragic. The first, made famous by the book and movie Black Hawk Down, occurred in 1993, during the U.S. intervention in the civil war in Somalia. A second took place on March 4, 2002, five months into the war in Afghanistan, on the peak of Takur Ghar—the first operation in which the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment and armed Predators both took part, though not by design.

Fog of War

Mack was at the controls of one of two 160th MH-47Es assigned to take Navy SEALs to the base of Takur Ghar. The SEALs were to climb the mountain in darkness and set up a covert observation post overlooking the valley.

Things began to go wrong when mechanical problems with one helicopter delayed departure, leaving the SEALs too little time to climb the mountain before first light. During the Soviet occupation, Afghan rebels had created hide sites, bunkers, and fighting positions all over the Shah-i-Kot Valley and its mountains. But the leader of the SEAL team had told Mack there was no evidence of enemy forces on Takur Ghar. When he asked Mack to take the SEALs to the top of the mountain, Mack reluctantly agreed.

As he flared his Chinook to land the first group of SEALs on Takur Ghar’s snow-covered peak at about 3 am, “I caught sight of a rocket-propelled grenade flying at us,” Mack wrote in his book. The grenade hit just behind Mack’s seat, knocking out much of the Chinook’s electronic gear and its electric-powered mini-guns and starting a fire in the cabin. As Mack jerked the helicopter upward to fly away, one of the SEALs, Petty Officer First Class Neil Roberts, fell or jumped off the open back ramp. Mack told the crew they would return for Roberts, but with the Chinook’s engines now underpowered and its flight controls crippled by a transmission spewing hydraulic fluid from bullet holes, that proved impossible. Mack was barely able to fly the Chinook to a rough landing at the base of the mountain to await their own rescue.

Two hours later, at about 5 am, another Night Stalker Chinook helicopter dropped the SEALs back on Takur Ghar in a futile attempt to rescue Roberts, who as it turned out was already dead (in honor of the fallen SEAL, American troops now informally refer to Takur Ghar as Roberts Ridge). This Chinook, though also badly shot up on landing, managed to fly away. But under heavy enemy fire, the SEALs were forced to retreat down the side of the mountain. Air Force Technical Sergeant John Chapman, a combat controller who was attached to the SEALs to communicate with aircraft and call in close air support, was badly wounded and presumed dead (subsequent investigations indicating that Chapman fought for another hour have been a point of contention in the military community).

At about 6:10 am, with the sun coming up, a third Chinook landed on Takur Ghar, this one carrying a Quick Reaction Force of Rangers sent by what Naylor described in his 2015 book, Relentless Strike, as a “confused” headquarters commanding Operation Anaconda from an island off the coast of Oman. Unaware they were landing in a hornet’s nest, the helicopter that brought the Rangers was met with a barrage of bullets and rocket-propelled grenades. A crew chief and a Ranger were killed, and a pilot and another crew chief were wounded as they landed. Two more Rangers were shot dead as they stepped off the back ramp. The others scrambled for cover behind rocks to one side of the aircraft.

The catastrophic scene was witnessed as it unfolded through the camera of an armed Predator, tail number 3037, being flown about 12 miles from Takur Ghar by a pilot and sensor operator some 7,000 miles away. They were stationed in one of two ground control stations on the CIA’s campus in northern Virginia, next to a double-wide mobile home used as the operations center. With approval from higher-ups, the joint CIA-Air Force team, which used the radio call-sign “Wildfire,” would soon play a major role in the Battle of Takur Ghar.

The air crew of Razor 03, who attempted to insert a reconnaissance team at Takur Ghar.

“Basically, we rubbernecked into one of the biggest fights in Afghanistan,” wrote Mark Cooter, a retired Air Force colonel, and Alec Bierbauer, described as the “CIA’s point man in the development of the Predator program,” in their 2021 memoir Never Mind, We’ll Do It Ourselves. The two men were the operational leaders of the Air Force and CIA Predator team at the “Trailer Park,” as they jokingly called it, whose members were flying the only two armed Predators in existence, tail numbers 3034 and 3037, having lost a third—number 3038—to a communications failure early in the war.

Two different Wildfire crews and their commanders watched and listened via radio as Air Force Staff Sergeant Gabriel Brown, a combat controller with the Rangers on Takur Ghar, worked desperately to direct fighter aircraft in bombing and strafing runs at the enemy bunker. With bullets snapping through the air around him, having to shout over gunfire as the Rangers fought, trying above all to be sure the bombing and strafing runs didn’t hit his side in the fight, it took Brown some time to realize that one of the voices using his call-sign, Slick Zero One, and offering help was a Predator pilot using the call-sign Wildfire 54.

“I was calling him, saying, ‘Hey, Slick, this is Wildfire,’ ” recalled the Predator pilot, who wishes to be identified only as “Big” (his radio moniker in 2002). “ ‘I’ve got those guys at the helicopter’s two o’clock underneath that tree,’ ” Big recalled telling Brown. “ ‘I’ve got two Hellfires. I can take them out for you.’ ”

Three weeks earlier, Brown had seen a news article reporting that an armed Predator had taken out a target in Afghanistan, but that was all he knew about the new weapon. “He kept selling it, and I took the bait,” says Brown.

By 2009, the Night Stalkers had their own armed-drone unit, Echo Company, which flies the MQ‑1C Gray Eagle. This drone is powered by a heavy-fuel engine for higher performance, better fuel efficiency, and a longer lifetime.

For reasons participants disagreed on years later, Big and his sensor operator—whose job in part was to use a laser designator to guide the Hellfire to its target after the pilot launched it—put their first shot into a tree near the enemy bunker. But the second Hellfire destroyed the bunker.

That was a turning point, though not the end of the battle. With higher-ups unwilling to risk more helicopters in daylight, the Rangers were stuck on the mountaintop all day, taking mortar and small-arms fire from remaining enemy fighters as Senior Airman Jason Cunningham, a pararescueman, slowly died of wounds received while he was administering trauma care to others.

Brown called in other fighters and the Predator crew used their laser designator to “buddy-lase” bomb runs that killed or held off many enemy combatants. They also used their camera to spot enemy movements and alert the Rangers.

After darkness fell, the Predator’s laser illuminator served as a sort of infrared flashlight whose beam was visible through night vision goggles—enabling the Rangers to see around them. The illuminator also guided two Chinooks that flew in at 9:15 pm to pick up all the Americans at Takur Ghar, including the seven troops killed.

Reports of the armed Predator’s role at Takur Ghar inspired the Air Force to begin arming its own fleet of Predators shortly before the 2003 Iraq War. Soon, 160th pilots and many others in the U.S. military came to rely on the MQ-1. By 2009, the Night Stalkers had their own armed drone unit, Echo Company, flying a Predator derivative built by General Atomics—the MQ-1C Gray Eagle.

It’s a partnership that began on a mountaintop in Afghanistan, and it will long be commemorated with Predator 3034 and a Night Stalker uniform displayed at the National Air and Space Museum.

Richard Whittle, a former Verville Fellow at the National Air and Space Museum, is the author of The Dream Machine: The Untold History of the Notorious V-22 Osprey and Predator: The Secret Origins of the Drone Revolution.

This article, originally titled "Night Stalkers Down," is from the Fall 2025 issue of Air & Space Quarterly, the National Air and Space Museum's signature magazine that explores topics in aviation and space, from the earliest moments of flight to today. Explore the full issue.

Want to receive ad-free hard copies of Air & Space Quarterly? Join the Museum's National Air and Space Society to subscribe.

Related Topics

You may also like

Related Objects

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Support the Museum

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.